As the temperatures turn cooler here in the northern hemisphere, I’ve begun to receive an increased number of communications regarding the identities of spiders that were recently noticed in someone’s house. They’ve likely always been there, of course – spiders that commonly live out-of-doors don’t generally seasonally migrate indoors as autumn approaches, it’s just that this tends to be the time of mating for a number of the common indoor species and the males become more active, and thus visible, as they roam about seeking potential mates.

But in any case, what with the increased movement of spiders around northern homes, and so many people being more often in said homes during this present year of confining pestilence and thus noticing them, questions – and fears – proliferate. It’s likely preaching to the proverbial choir to state here that most species of spiders are not of any significant threat to humans, or that having a population of spiders living in one’s home is beneficial as they commonly prey upon many of the arthropods that may pose risks to person or property. Yet in any case, being able to sort out the spiders seen in the course or daily life – whether indoors or out – is a handy skill for both the naturalist and non-naturalist alike. To the end of which, I’d like to recommend a few helpful guidebooks to which I’ve found it useful to turn whenever I’m seeking the identity of an unknown arachnid.

For those in North America, my immediate “go-to” for all spider questions is Common Spiders of North America by Richard A. Bradley and Steve Buchanan. Originally published in hardcover in 2012 by University of California Press, a paperback edition was brought into print by the same publisher in 2019, making this remarkably useful book more easily and affordably available to all interested readers. Being the “first comprehensive guide to all 68 spider families in North America beautifully illustrates 469 of the most commonly encountered species,” this is a very accessible book with a variety of helpful keys and other information to allow effective identification of the included species by sight.

For those in North America, my immediate “go-to” for all spider questions is Common Spiders of North America by Richard A. Bradley and Steve Buchanan. Originally published in hardcover in 2012 by University of California Press, a paperback edition was brought into print by the same publisher in 2019, making this remarkably useful book more easily and affordably available to all interested readers. Being the “first comprehensive guide to all 68 spider families in North America beautifully illustrates 469 of the most commonly encountered species,” this is a very accessible book with a variety of helpful keys and other information to allow effective identification of the included species by sight.

For those along the Pacific Coast, another book to which I often turn is the Field Guide to the Spiders of California and the Pacific Coast States by Richard J. Adams and Timothy D. Manolis. Also published by University of California Press as part of their landmark California Natural History Guide series, this handy guidebook includes information about “all of the families and many of the genera found along the Pacific Coast, including introduced species and common garden spiders.” Reference keys allow quick and effective identification to the taxonomic family level, and often beyond that to the genus and even species.

For those along the Pacific Coast, another book to which I often turn is the Field Guide to the Spiders of California and the Pacific Coast States by Richard J. Adams and Timothy D. Manolis. Also published by University of California Press as part of their landmark California Natural History Guide series, this handy guidebook includes information about “all of the families and many of the genera found along the Pacific Coast, including introduced species and common garden spiders.” Reference keys allow quick and effective identification to the taxonomic family level, and often beyond that to the genus and even species.

Then, for those “down east” up in Maine, I’ve recently been made aware of a new book, Dana Wilde’s A Backyard Book of Spiders in Maine. Published by North Country Press, this ground-level guidebook focuses on spiders likely to be spotted in Maine. Wilde presents clearly written and informative profiles – accompanied by very useful images, primarily from his own camera – of forty-two species, as well as a number of additional genera, of spider that anyone may reasonably expect to find in the course of exploring the natural world throughout the Pine Tree State.

Then, for those “down east” up in Maine, I’ve recently been made aware of a new book, Dana Wilde’s A Backyard Book of Spiders in Maine. Published by North Country Press, this ground-level guidebook focuses on spiders likely to be spotted in Maine. Wilde presents clearly written and informative profiles – accompanied by very useful images, primarily from his own camera – of forty-two species, as well as a number of additional genera, of spider that anyone may reasonably expect to find in the course of exploring the natural world throughout the Pine Tree State.

Hoping the Atlantic to the Scepter’d Isle, Britain’s Spiders: A Field Guide by Lawrence Bee, Geoff Oxford, and Helen Smith, published by Princeton University Press‘ WildGuides imprint as part of their Britain’s Wildlife series and in partnership with the British Arachnological Society, provides what has since 2017 been the essential guide to the spiders of Great Britain. Covering all thirty-seven of the British families, and focusing on spiders that can be identified in the field, this must-have guidebook includes descriptions and images of 395 of Britain’s approximately 670 species, with the limitations to field identification clearly explained.

Hoping the Atlantic to the Scepter’d Isle, Britain’s Spiders: A Field Guide by Lawrence Bee, Geoff Oxford, and Helen Smith, published by Princeton University Press‘ WildGuides imprint as part of their Britain’s Wildlife series and in partnership with the British Arachnological Society, provides what has since 2017 been the essential guide to the spiders of Great Britain. Covering all thirty-seven of the British families, and focusing on spiders that can be identified in the field, this must-have guidebook includes descriptions and images of 395 of Britain’s approximately 670 species, with the limitations to field identification clearly explained.

In fact, this remarkable field guide has been so popular since its original release that a fully revised and updated second edition of it covering an increased number of species that brings the total to 404 was published to great acclaim this past August in the U.K., and is scheduled to become available in North America in November 2020. No copy of this new second edition has yet reached me (I was expecting to see it for the first time at the BirdFair 2020, which was held only online due to CoVid-19 restrictions), however if the original edition is any standard of what to expect, it is difficult to imagine how they could have further improved it – yet I have every reason to beleive they very likely have.

In fact, this remarkable field guide has been so popular since its original release that a fully revised and updated second edition of it covering an increased number of species that brings the total to 404 was published to great acclaim this past August in the U.K., and is scheduled to become available in North America in November 2020. No copy of this new second edition has yet reached me (I was expecting to see it for the first time at the BirdFair 2020, which was held only online due to CoVid-19 restrictions), however if the original edition is any standard of what to expect, it is difficult to imagine how they could have further improved it – yet I have every reason to beleive they very likely have.

For those seeking a general (that is, non-specialist) field guide to spiders for continental Europe, the only English language one of which I am presently aware is Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe by Michael J. Roberts. Published by Harper Collins UK in 1999, this increasingly difficult-to-locate guidebook includes illustrated descriptions of 450 species found in the title range, as well as web illustrations and details of genetalia for all included species to allow positive identification. It should also be noted that contents of this guidebook have been translated into French by Patrice Leraut and published as Araignées de France et d’Europe by Delachaux et Niestle.

For those seeking a general (that is, non-specialist) field guide to spiders for continental Europe, the only English language one of which I am presently aware is Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe by Michael J. Roberts. Published by Harper Collins UK in 1999, this increasingly difficult-to-locate guidebook includes illustrated descriptions of 450 species found in the title range, as well as web illustrations and details of genetalia for all included species to allow positive identification. It should also be noted that contents of this guidebook have been translated into French by Patrice Leraut and published as Araignées de France et d’Europe by Delachaux et Niestle.

And for those seeking a guide to the spiders of Germany and surrounding countries, Kosmos offers two volumes as part of their superb Naturführer series. Der Kosmos Spinnenführer by Heiko Bellmann, includes illustrated descriptions for over 400 European species, and Welche Spinne ist das?, a pocket-sized volume of their Kosmos Basic category that depicts and describes 132 of the most commonly seen and easily identifiable species. (As a personal aside, even though my German language skills are rudimentary, I have nonetheless made it a point to pick up at least one of the Kosmos Naturführer series each time I’ve visited Germany – they are superb and have proven themselves useful time and again even to one such as myself with limited ability in their language of publication.)

And for those seeking a guide to the spiders of Germany and surrounding countries, Kosmos offers two volumes as part of their superb Naturführer series. Der Kosmos Spinnenführer by Heiko Bellmann, includes illustrated descriptions for over 400 European species, and Welche Spinne ist das?, a pocket-sized volume of their Kosmos Basic category that depicts and describes 132 of the most commonly seen and easily identifiable species. (As a personal aside, even though my German language skills are rudimentary, I have nonetheless made it a point to pick up at least one of the Kosmos Naturführer series each time I’ve visited Germany – they are superb and have proven themselves useful time and again even to one such as myself with limited ability in their language of publication.)

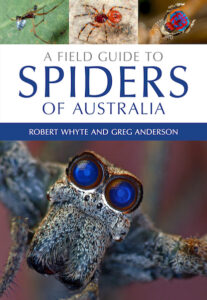

Finally, even though it is the beginning of spring rather than autumn in the land down under, I would feel remiss if I didn’t mention one of the most vividly illustrated field guides to spiders it has ever been my pleasure to read: Robert Whyte’s and Greg Anderson’s A Field Guide to the Spiders of Australia from CSIRO Publishing. Containing over 1,300 color images of some of the world’s most astonishingly beautiful spiders, it is the most comprehensive field guide to Australia’s spiders yet published. And to make it even more intriguing, it should be remembered that an estimated two thirds of that land’s spiders have yet to be identified and described – making readers naturally ask the question “What else is out there?” This is unquestionably the essential guidebook for anyone living in, visiting, or simply interested in Australia’s amazing arachnids.

Finally, even though it is the beginning of spring rather than autumn in the land down under, I would feel remiss if I didn’t mention one of the most vividly illustrated field guides to spiders it has ever been my pleasure to read: Robert Whyte’s and Greg Anderson’s A Field Guide to the Spiders of Australia from CSIRO Publishing. Containing over 1,300 color images of some of the world’s most astonishingly beautiful spiders, it is the most comprehensive field guide to Australia’s spiders yet published. And to make it even more intriguing, it should be remembered that an estimated two thirds of that land’s spiders have yet to be identified and described – making readers naturally ask the question “What else is out there?” This is unquestionably the essential guidebook for anyone living in, visiting, or simply interested in Australia’s amazing arachnids.

I have not, it will certainly be noted by some, included any works in this essay that take the more general natural history of spiders as their subject. That was intentional as I wanted to keep the focus here on field guides specifically. I will, another time, examine and present a list of worthwhile books for those seeking to delve more deeply into the lives and behaviors of member of the Order Araneae either as a whole or in substantial part. Until then, consider picking up one of these helpful guide books presented here and take advantage of their season of high activity to learn the identities of and a bit more about your local spiders.