Following the introduction of the bill defining the Endangered Species Act to the United States Senate by Sen. Harrison A. Williams (D-NJ) on 12 June 1973, the Senate unanimously approved it less than a fortnight later on 24 July. Following this, by a vote of 390-12 the U.S. House of Representatives approved a version of the bill on 18 September of that same year. As protocol directs, a joint conference committee was then convened to reconcile the Senate and House versions. The conference committee reported the bill on 19 December 1973 and on that same day the House and the Senate both approved the resulting legislation. President Richard M. Nixon (R) – yes, you read that correctly – signed the Endangered Species Act into law on 28 December 1973. Not only was the scope of the Act truly visionary, the level of bipartisan support that made its enactment possible is all but unimaginable in light of the present-day monument to partisanship, pettiness, and nincompoopery that calls itself the current U.S. Congress.

Following the introduction of the bill defining the Endangered Species Act to the United States Senate by Sen. Harrison A. Williams (D-NJ) on 12 June 1973, the Senate unanimously approved it less than a fortnight later on 24 July. Following this, by a vote of 390-12 the U.S. House of Representatives approved a version of the bill on 18 September of that same year. As protocol directs, a joint conference committee was then convened to reconcile the Senate and House versions. The conference committee reported the bill on 19 December 1973 and on that same day the House and the Senate both approved the resulting legislation. President Richard M. Nixon (R) – yes, you read that correctly – signed the Endangered Species Act into law on 28 December 1973. Not only was the scope of the Act truly visionary, the level of bipartisan support that made its enactment possible is all but unimaginable in light of the present-day monument to partisanship, pettiness, and nincompoopery that calls itself the current U.S. Congress.

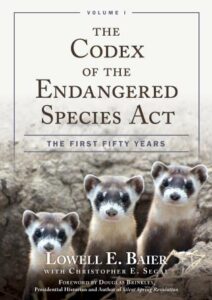

Fifty years later, more than 1,600 species are listed and therefore protected under the provisions of this remarkable piece of bipartisan legislation. Over the decades of its existence, such iconic species as the Bald Eagle, the Gray Whale, the Mexican Gray Wolf, and the Black-footed Ferret have all seen their species’ health improved thanks to it. This it is particularly fitting that the last mentioned of these graces the cover of The Codex of the Endangered Species Act; Volume I – The First Fifty Years, the first of two volumes written by Lowell E. Baier and published during the Act’s golden anniversary year of 2023 that offers interested readers the most comprehensive single-volume overview yet published of its first fifty years (and at 864 pages, I do mean comprehensive).

Yet don’t let the length intimidate you. While I haven’t completed a full reading of this monumental work at the time of this writing, I am well on my way to doing so and can most confidently state that far from being a dry academic or legal tome riddled with jargon and narrative-interrupting citations in each sentence, Mr. Baier’s recounting of this history is a lively and compelling narrative journey through half a century of American conservation history. Indeed, it’s a journey everyone interested in the subject of endangered species conservation should consider as an imperative to make.

The Codex of the Endangered Species Act; Volume II – The Next Fifty Years – The Well-read Naturalist

January 16, 2024 @ 00:02

[…] you finish reading Lowell Baier’s monumental new book The Codex of the Endangered Species Act; Volume I – The First Fifty Years, you’ll likely have found yourself completely caught-up in the story and will be asking […]

A Few Late Night Thoughts Reading Lowell Baier’s New Codex – The Well-read Naturalist

January 19, 2024 @ 00:02

[…] Lowell Baier’s The Codex of the Endangered Species Act – The First Fifty Years is proving to be not only remarkably enlightening but also surprisingly emotionally recuperative. […]