As a former commercial salmon fisherman, as well as the son and grandson of commercial salmon fishermen, I’ve long found the placement of boundaries around which species of wildlife are allowed to be harvested for commercial sale, which for personal consumption, and which prohibited from any form of commerce to be somewhat arbitrary. In the U.S. today, for example, most fish are allowed – with appropriate licenses where required, of course – to be caught for personal consumption and a smaller but still significant number also for commercial sale, whereas only a few dozen bird species and perhaps a dozen mammal species are allowed to hunted by licensed individuals but none allowed to be sold commercially; however many of those same species are allowed to be bred and raised on farms for commercial slaughter and sale in some states. The more one thinks about it, the more peculiar such boundaries seem to be.

As a former commercial salmon fisherman, as well as the son and grandson of commercial salmon fishermen, I’ve long found the placement of boundaries around which species of wildlife are allowed to be harvested for commercial sale, which for personal consumption, and which prohibited from any form of commerce to be somewhat arbitrary. In the U.S. today, for example, most fish are allowed – with appropriate licenses where required, of course – to be caught for personal consumption and a smaller but still significant number also for commercial sale, whereas only a few dozen bird species and perhaps a dozen mammal species are allowed to hunted by licensed individuals but none allowed to be sold commercially; however many of those same species are allowed to be bred and raised on farms for commercial slaughter and sale in some states. The more one thinks about it, the more peculiar such boundaries seem to be.

Not so long ago, commercial harvesting of birds and mammals was more akin to that of commercial seafood harvesting. More species were allowed to be hunted and sold into the marketplace, either for food or for the use of some part of them for some other purpose, as well as captured captured alive for various other uses. It was a market the sprang up relatively quickly in the rapidly growing U.S. of the nineteenth century, and thanks to its excesses, became a pariah in many quarters and was legislated out of existence almost as fast in the twentieth century, leaving as its primary legacy the modern wildlife conservation movement.

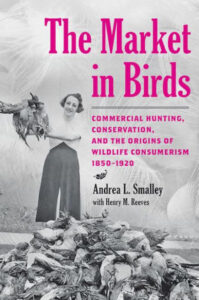

In their new book The Market in Birds; Commercial Hunting, Conservation, and the Origins of Wildlife Consumerism, 1850–1920, Prof. Andrea L. Smalley and retired wildlife biologist Henry M. Reeves examine the history of the commercial U.S. market in wild birds through the period that saw the rise and decline of this now famously infamous collection of trades. From market hunting to millinery, the demand for both food and feathers fueled pressure on the populations of hundreds of bird species, leading to the decline of many and even the extinction of a few.

While many bird watchers, wildlife conservation enthusiasts, and others interested in the history of natural history of the nineteenth and twentieth century United States will be familiar with some of the more popularly publicized episodes of commercial bird hunting and commercial excesses of this period, this new book promises to delve much deeper than most popular presentations of the subject, examining the many intersecting forces of the time in order to provide a much more rich understanding of it to all those – including myself – who wish to expand and refine their knowledge of what was truly a pivotal time in the history of wildlife conservation and management.