To borrow a few lines from Joni Mitchell’s arguably most famous song, “Don’t it always seem to go / That you don’t know what you got / ’Til it’s gone / They paved paradise / And put up a parking lot.” However when it comes to Idaho’s Silver Valley district, a century of mining for silver, lead, zinc, and other metals didn’t so much cause paradise to be paved as dug up, sifted and strained, and the remains dumped into the Coeur d’Alene River.

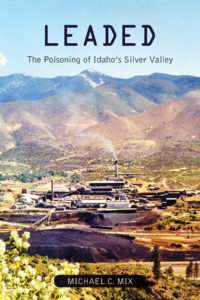

“Nearly the entire range of the Coeur d’Alene mountains, clothed with evergreen forests, with here and there an open summit covered with grass; numerous valleys intersecting the country for miles around; courses of many streams, marked by the ascending fog, all conduced to render the view fascinating in the greatest degree to the beholder…” So quotes Michael C. Mix, author of Leaded; the Poisoning of Idaho’s Silver Valley, from the writings of Isaac Stevens, first governor of the Washington Territory, who passed through and described the region in 1853. Stevens, as well as another quoted visitor in the 1840s, the pioneer botanist Charles Geyer, painted a picture of a verdant wonderland of mountains and valleys stretching as far as the eye could see. However beneath all those trees, under the mountains, lay vast deposits of the very metals a rapidly industrializing nation desired.

Initially it wasn’t the silver, the lead, or the zinc that caused the first mining camps to be established; it was gold. Prospectors had been exploring northern Idaho since the middle of the Nineteenth Century with enough success to keep them there but not enough to make anyone particularly wealthy. Had it not been for the discovery of multiple deposits of lead, zinc, and silver in 1884, the gold prospectors, seeing as they were diminishing returns for their efforts, may likely have soon given up and left, leaving the mountains and valleys not so very different than they had found them. Alas, the white metal lodes changed everything.

As Mix explains, over the course of the next hundred years, miners in the Silver Valley would extract from the earth “nearly 7.5 million tons of lead, four million tons of zinc, one billion ounces of silver, and smaller amount of copper and gold, worth almost $5 billion.” Vast corporate fortunes would be made, the landscape would be forever changed, and the worst case of mass lead poisoning ever recorded in the United States would occur, be tried in the courts, and begin to open the eyes of the nation to the dangers of large scale industrial pollution.

Leaded depicts an American west that few of us likely have previously encountered in either books or films; an American west not of vast open plains and cattle drives but of ramshackle mining camps evolving into seemingly-impermanent-yet-permanent towns under the shadow of ever-expanding industrial facilities pouring toxic smoke into the air as valuable metals were separated from the rocks in which they were contained. It’s a west of labor unrest, violent strikes, equally strike-breaking, corruption, collusion, and environmental destruction. And most importantly for how its history played out, it’s a land where pollution regulations are not merely lax, they literally don’t yet exist.

Farmers whose crops and stock were damaged or killed by the water or air polluted as a result of the smelting operations found themselves on the losing end of lawsuits due to the Idaho constitution being on the side of industry, giving it the right to the lands and waters ahead of the people. It was a time of unquestioned national expansion; a time of making America great – regardless of the cost to those doing the work or the earth from which the wealth was taken.

It wouldn’t be until after the Second World War that the first national environmental protection act would be enacted, and not until decades later when the beginnings of an effective enforcement body would be created to see that such protective laws were being followed. For decade upon decade, the Coeur d’Alene river and other bodies of water in the area would be filled with the tailings of the mines, and the hap-hazard development and “mining camp” ethos of the towns where the workers and their families lived would allow these tailings to be mixed with raw sewage that flowed from incomplete sewer systems, or sometimes simply from pipes directly from homes into the waterways.

Then, of course, there was the lead poisoning. For decades, particles of lead and other metals flowed from the stacks of the smelters in such quantities to raise the blood lead levels of the region’s people and animals to dangerous levels. Originally, the problem was that no one knew just how much lead in the blood was truly dangerous. For years, anything less than obvious physical signs of lead poisoning was not thought to be harmful. However as the years passed, and as independent researchers began to discover that lower blood lead levels also caused significant health problems, the “not knowing” shifted from genuine to willful ignorance.

Following the advice of their own hired experts, companies implemented policies that blamed the workers for their own health problems. If an employee’s blood lead levels were found to be high, it must be due to that person not following the company’s safety policies. And if the employee’s spouse and children also had high lead levels, it was because the employee contaminated them. Couple this attitude with a determined reliance by the mining companies on testing procedures that were considered by independent experts to be insufficient to obtain accurate results, and the problem was allowed to continue for decades.

It is in following the events, studies, and legal cases that finally set the stage for a reckoning on the part of the region’s largest mining company, Bunker Hill, that Mix particularly excels in Leaded. Having already provided a thorough history of the area’s development as a preëminent mining location, he shifts – still not abandoning the rigorously detailed manner in which he has recounted the history thus far – into a slightly more narrative style, bringing the reader closer to the individual people who brought the legal cases that determined if an industrial polluter can be held accountable in America for the damage their operations caused.

At a time in American history when the nation is now torn in half over the direction it will take, when we have for so long now enjoyed the protections of the law from the over-reaching avarice of industries that have it within their power to lay waste to the land and its people in pursuit of their own profits, when we are being harangued to put aside these protections in order to allow unimaginably profitable multi-national businesses to do whatever they deem best under the banner of making America great again, it is imperative that we turn and look at the destruction that lies strewn in the path we have travelled this past century and how far we have now come away from its darkest parts. Michael Mix’s Leaded very clearly shows us how it once was to live in a land where the rights of businesses to take from the land surmounted the rights of the people to live in safety and health upon it, and from it we should take heed lest it someday be visited upon us again.

Title: Leaded; The Poisoning of Idaho’s Silver Valley

Title: Leaded; The Poisoning of Idaho’s Silver Valley

Author: Michael C. Mix

Publisher: Oregon State University Press

Format: Paperback

Pages: 280 pp.

ISBN 978-0-87071-875-5

Published: November 2016

In accordance with Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR Part 255, it is disclosed that the copy of the book read in order to produce this review was provided gratis to the reviewer by the publisher.