As one who not only grew up in a rural area where hunting is as much a normal part of life as going to school, having a job, or raising a family, but who also spent a decade working for one of the world’s most well known hunting equipment companies – Leupold – I likely have a somewhat different perspective on it than many modern naturalists. However on the other hand, I likely also have a perspective on hunting that may be a bit more recognizable to the naturalists of yore whose tools often included a shotgun or rifle. Yet be that as it all may, I have one fairly basic rule that I learned from my father when I was a boy that I apply when assessing any type of hunting: are you going to eat what you shoot?

I have, of course, had to make allowances for researchers collecting specimens – something neither my father nor I knew anything about all those years ago – and for the necessity of those managing large tracts of agricultural land when predator control can be accomplished by no other viable options; but for the rest, the question is universally applied. Not surprisingly, this has at various times put me at odds with big game trophy hunters, game ranch hunters, and most recently fox hunters. It has also brought about arguments with anti-hunting activists who proclaim that no hunting of any form should ever take place.

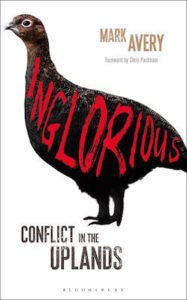

So when I took up Mark Avery’s book Inglorious; Conflict in the Uplands, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I knew Avery to be an ardent conservationist as well as a researcher of impeccable credentials, but I also knew him to be a person of very deep convictions – something I have often seen get the better of even the most intelligent and rational people in the past. That he was opposed to grouse hunting I assumed – although just what grouse “shooting” (he is, as I learned from the book, absolutely correct in refusing to call it hunting himself as it resembles genuine hunting no more than the canned hunts perpetrated as posh lodges throughout the American southwest and Texas) actually was I had yet to learn. But beyond the simple “eat what you kill” or ethical arguments, what more really was there to say in opposition to it?

As it turned out, plenty. With a style that flows smoothly back and forth between fact-based objective rationality and friendly, over-a-pint, good humor, Avery leads the reader through the history of upland estates, the natural history of Red Grouse, Hen Harriers, and moorlands, recent organizational and governmental activities surrounding driven grouse shooting and raptor conservation, and concludes with a detailed reflection on the year 2014 – when so much came to a head regarding the protection of Hen Harriers. When the last page was finally turned and the cover closed, I discovered that I was in possession of not only far more information on driven grouse shooting that I ever thought possible but more importantly a greatly enlarged understanding of how such seemingly isolated topics are interconnected to far more wide-reaching ones. And, of course, with knowledge comes questions – most significantly, for whom, and to what ends, are wild creatures and their habitats managed and conserved?

For those who may be unfamiliar with the practice of driven grouse shooting, it involves small numbers of shooters who pay large sums of money to be placed in advantageous positions on private estates where Red Grouse numbers have been carefully cultivated to be as high as possible through the elimination of any perceived natural predator of them – particularly raptors such as Hen Harriers – and from said positions fire as many shots as possible (switching between shotguns to speed the reloading process) in the direction of grouse being chased toward them by estate staff. The daily number of grouse killed during these shoots far exceeds what can, or will, be eaten by anyone involved.

While obviously elitist and wasteful in the extreme, grouse shooting estates have become a significant economic factor in the areas where they exist, which is what makes the subject such a tricky one. It’s one thing simply to say “It’s just a damned silly, antiquated past-time of a few excessively rich people with nothing better to do” but it’s quite another matter entirely when the economic inter-relationships of the grouse estates with their surrounding areas – to say nothing of the reach that the people who own these estates have into the political life of the nation – are considered. And that is Avery’s point – driven grouse shooting isn’t just an innocuous left-over from the by-gone age of country estates, it’s the focal point for a number of nationally, and even internationally significant conservation and financial challenges.

More than once during my reading of Inglorious I found myself thinking the conflict not wholly unlike that of the one between American ranchers and deer hunters, and those seeking to reintroduce or strengthen already existing wolf populations in the United States. Despite the differences between how shooting sports are practiced between the two countries – hunting in America being wide-spread and accessible to most anyone who cares to engage in it whereas grouse shooting (and all other gun sports) in England and Scotland is the exclusive purview of the wealthy – the central question is one of land and game management. Red Grouse on shooting estates are managed (with, among other techniques, the attempted elimination of real and perceived predators) to become severely out of proportion to their natural population numbers and deer populations, particularly White-tailed Deer, are similarly grossly inflated through management practices for the benefit of hunters in the U.S. The difference, of course, is that grouse shooting in the U.K. is practiced by a few thousand people at most – none of whom rely on it for food – whereas deer hunting in the U.S. is practiced by millions, the vast majority of whom eat everything they shoot. Nevertheless, what makes both possible is unnaturally inflated numbers of their target (pardon the pun) animal at the expense of all others, which once again raises the question, for whom and to what purpose is a nation’s wildlife managed?

Make no mistake, Mark Avery’s Inglorious is not a “light read;” some chapters are so richly filled with information that a straight-through reading is out of the question even by the most ardent of readers. But then for what he has to say it’s better to read slowly and in multiple sittings so that his observations and analyses can sink in more deeply. Indeed, many’s the night I climbed into bed and drifted off to sleep with a passage of Avery’s prose turning itself over and over again in my mind, creating new and more nuanced ideas out of what were before merely disconnected thoughts. To read Inglorious is to allow yourself to be challenged; challenged to think deeply, to interweave what were previously unconnected bits of information into intricate tapestries of understanding, to seek answers to questions that extend far beyond the upland heathered moors and into the heart of just what the conservation of nature truly means. It’s a challenge well worth accepting.

Title: Inglorious; Conflict in the Uplands

Title: Inglorious; Conflict in the Uplands

Author: Mark Avery, introduction by Chris Packham

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Format: Hardback

Pages: 304 pp.

Published: July 2015

ISBN: 9781472917416

In accordance with Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR Part 255, it is disclosed that the copy of the book read in order to produce this review was provided gratis to the reviewer by the publisher.

February 24, 2016 @ 19:32

Thank you for the suggestion.

Review of Inglorious from the USA - Mark AveryMark Avery

February 27, 2016 @ 22:01

[…] I’ve sometimes wondered how Americans would react to Inglorious and now I know that at least one of them has got the message – it’s a good start as that American is John Riutta also known as The Well-read Naturalist who reviews Inglorious on his excellent website. […]

Sunday book - but not a review - Mark AveryMark Avery

July 29, 2017 @ 22:02

[…] John Riutta, The Well-Read Naturalist: ‘To read Inglorious is to allow yourself to be challenged; challenged to think deeply, to interweave what were previously unconnected bits of information into intricate tapestries of understanding, to seek answers to questions that extend far beyond the upland heathered moors and into the heart of just what the conservation of nature truly means. It’s a challenge well worth accepting.‘ see full review here. […]